Politics and ethics don’t often seem to go together. But it is where the democracy reform process needs to start: demanding that our elected representatives are committed to a minimum set of ethical standards.

As we decry what many say is the most incompetent Government in living memory, it’s important not to fall into the trap of just waiting for it to be replaced, thinking all will be well henceforth. We need to look at how to avoid Australia ever having to experience this kind of dysfunction again. Just electing another party is not enough – like peeing in your pants to keep warm, feels good for a while until it goes cold or smelly or both.

Important as it is, setting up a Federal ICAC is dealing with the symptoms of a flawed system, not the root cause. Tinkering around the edges of donation regulation won’t change how vested interests have far too much influence over policy, nor will enforcing and strengthening the largely ignored rules for lobbyists’ behaviour.

A Labor led Government will reverse some of the worst excesses of the ATM gang, direct more of our collective wealth towards those in need and to the education sector, maybe even bring common sense back into our foreign policy. It will (hopefully) be brave enough to recognise the folly of turning back boats as a substitute for humane treatment of desperate refugees, and no doubt introduce real policies to help combat the effects of climate change.

Bill Shorten has pledged his support for the process towards finally removing our colonial shackles with our own Head of State, and “pursuing an indigenous voice in Parliament”, although we have yet to see how.

The latter two will require constitutional changes. Ideally so would the much needed introduction of a Bill of Rights, although (as former Human Rights Commissioner Gillian Triggs have pointed out) a bill protecting our basic rights to freedom of speech, the right to a fair trial, freedom from discrimination, equal right to education, protection of privacy, etc. – rights most of us take for granted – can be enacted by itself. At least as a starting point leading to it eventually being enshrined in a reformed Constitution.

As Triggs points out, Australia is the only “proper” democracy that doesn’t have a Bill of Rights.

We live in a world where democracy is under threat from elected leaders with disdain for the institutions of democracy, which makes it even more important to formalise our assumed rights. Australia is now only one of 19 countries ranked as “true” democracies by the Economist’s Democracy Index published earlier this year.

The latest edition of the index records the worst decline in global democracy for almost a decade. United States is not among the 19, but on a list of flawed democracies, mainly due to the low voter participation rate. And although our mandatory voting system holds us in good stead on that score, we have no reason to be complacent.

The “witness K” case shows that our Government (unopposed by Labor) can flout the basic rights of the people to hold it to account. The “it’s OK to be white” stunt in the Senate proves we have elected representatives failing to understand what’s at stake. Press freedoms are under threat by draconian laws limiting reporting from the refugee camps and Peter Dutton is working to broaden State surveillance, threatening privacy.

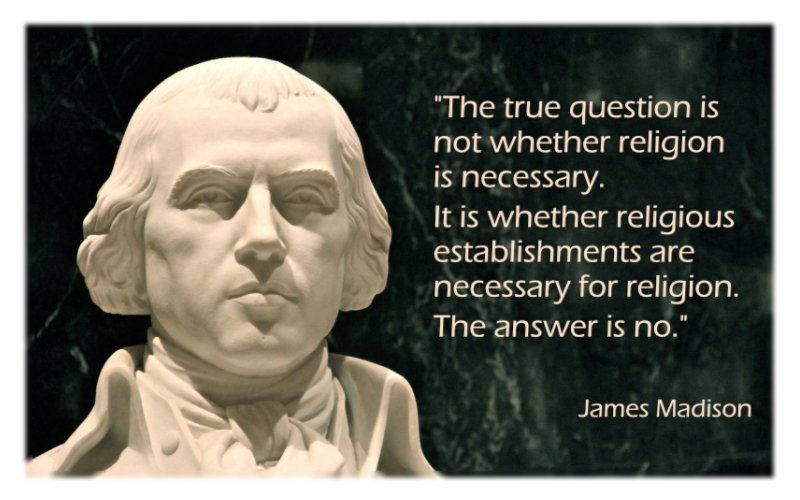

And as religion makes a return to the political debate, tolerance for those with a different view to our own continues its decline towards an ever increasing polarisation.

Religious freedom – and its logical antithesis freedom from religion – are the only rights specifically mentioned in our constitution (Section 116). Much to the chagrin of those calling for the “right” of religious education in State schools (as long as it their particular brand of religion, of course).

I have no problem with school children learning about the worlds many religions and their often violent history, but I would also love to see our children be taught the ideas of ethical behaviour from a humanistic perspective, free of religious dogma.

But more importantly, I want to see our elected representatives and those chosen for executive Government to adhere to basic ethical principles.

Politics and Ethics

“Ethics is knowing the difference between what you have a right to do and what is right to do.”

(Potter Stewart – former US Supreme Court Justice)

When the venerable Tony Fitzgerald and the Australian Institute put these seven basic questions of ethics to our parliamentarians in June 2017, 36 declined to take part and 137 did not reply. Less than one quarter of our federal politicians – including 39 from the ALP, an encouraging sign – were prepared to commit to these, fairly self-evident, standards of conduct:

1. To act honourably and fairly and solely in the public interest

2. To treat all citizens equally

3. To tell the truth

4. Not to mislead or deceive

5. Not to withhold or obfuscate information to which voters are entitled

6. Not to spend public money except for public benefit

7. Not to use your position or information gained from your position for your benefit or the benefit of a family member, friend, political party or other related entity

Reforming our democracy will be a long and arduous process. Changing current conventions is hard enough, and will be met with intense resistance from those with a vested interest in the status quo. Constitutional changes are even harder.

But all change starts with small steps. Demanding that those wanting to represent us in Parliament are prepared to sign up to a set of self-evident standards of ethical behaviour to be elected – and turn away from those that won’t – is one such small step.

Not only that, it’s a small step that doesn’t require changes to law, regulations, party programs, statutes or ballot papers. All it requires is consent by individuals of their free will in their own self-interest.